By the Sea, by the Sea, by the Beautiful Sea - of Cortez, that is!

Author: P. Pennywagon, Ph.D.Copyright © 2012 Mednansky Institute, Inc.

The Sea of Cortez, or the Gulf of California, is a long, narrow, highly dangerous body of water. It is subject to sudden and vicious storms of great intensity. The months of March and April are usually quite calm and dependable and the March-April tides of 1940 were particularly good for collecting in the littoral - from 'Sea of Cortez' by John Steinbeck and Edward Ricketts, 1941

Clipping from the San Francisco Call, Volume 68, Number 8, 8 June 1890

Published in 1941, Sea of Cortez: a leisurely Journey of Travel and Research is a collaborative volume, a narrative by John Steinbeck and scientific appendix by marine biologist Edward Ricketts. Steinbeck and Ricketts met in Monterey, California in 1930; they became close friends instantaneously. Ricketts owned 'Pacific Biological Laboratory, Inc.', a 'strange' commercial laboratory in Cannery Row, Monterey. In his moving tribute About Ed Ricketts1 Steinbeck wrote, "We worked together, and so closely that I do not now know in some case who started which line of speculation since the end thought was the product of both minds."

1An introductory memoir for the 1951 edition of the Steinbeck's narrative under the title The Log from the Sea of Cortez (Ricketts died in an automobile accident in May 1948)They collected marine animals together, a six-day trip in 1936 collecting octopuses along Baja California coast and collecting trips in 1939 in the San Francisco Bay. Sea of Cortez is based on Ricketts' journal of a six-week marine biological expedition in the Gulf of California during the March-April tides of 1940. "We made a trip into the Gulf; sometimes we dignified it by calling it an expedition" wrote Steinbeck in the Introduction of Sea of Cortez.

The Western Flyer, a seventy-six feet long ship with a twenty-five-foot beam, was taken on charter. And so they went, without pretense but knowing what they were searching for. "We search for something that will seem like the truth to us; we search for understanding; we search for that principle which keys us deeply into the pattern of all life; we search for the relation of things, one to another, as this young man searches for a warm light in his wife's eyes and that one for the hot warmth of fighting" (from Sea of Cortez Chapter 11).

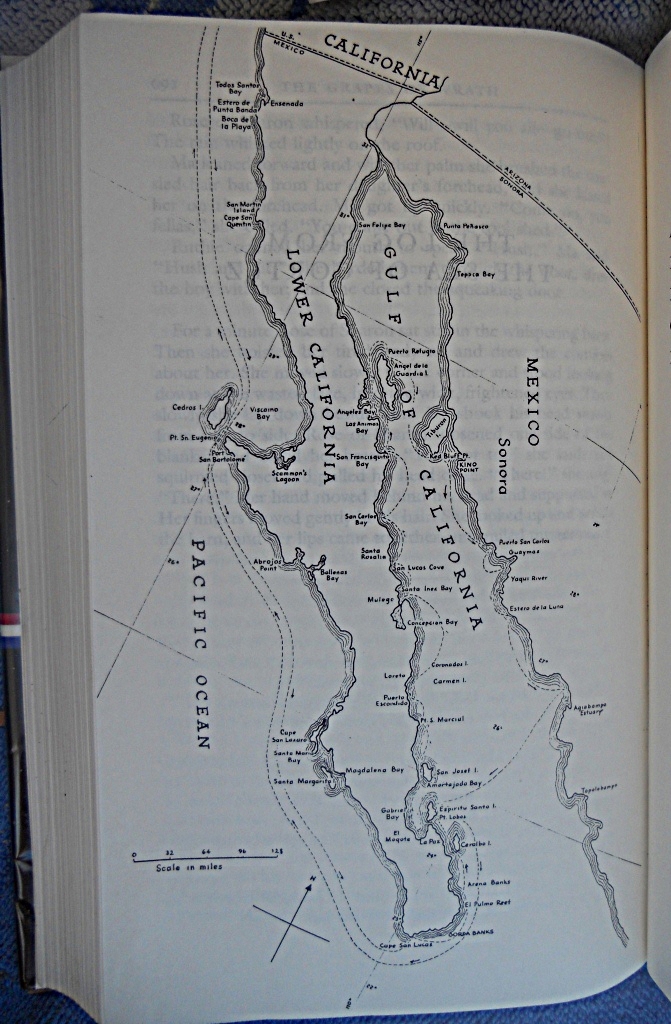

The Western Flyer route

They collected all sorts of marine life (isopods, crabs, urchins, sponges, cucumbers, tunicates, bivalves, snails, to cite a few), day or night, from one station to another, preserving and labeling while the boat was moving. Like young Darwin on the Beagle they wanted 'to see everything' their eyes would accommodate despite limited time, equipment and personnel. As mentioned, "We worked hard, but not beyond reason, and our wonder is caused not by the numbers [of animals] we took, but by the small numbers they [eight naturalists on an expedition in the Gulf thirty years before] did". It did not really matter to them, limited time, equipment and personnel, they said they "could not make much of a job of it" (6 weeks they had and even the boat hurried them) but they still did well with plenty of fervor, and they liked it. "We liked it very much" wrote Steinbeck in the final chapter of the book.

They found new species however their interest laid in the 'ecological perspective'. They analyzed biological assemblages (relationship of animal to animal, interdependence for food), kinds of environment (sand bottoms, shore boulders, racing tides, etc.), and ecological groups ("…groups melt into ecological groups until the time when what we know as life meets and enters what we think of as non-life… And the units nestle into the whole and are inseparable from it" - wrote Steinbeck in chapter 21). Immersed as they were in a web of intertwined units, they fathomed the mystical universal picture that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things. Comprehension of the whole would enforce understanding of the relational picture; they thought of it as 'the real because': it is so because it is so. Thus unfolds the story of the willow grouse as a fable (reported in Chapter 14): "At one time an important game bird in Norway, the willow grouse, was so clearly threatened that it was thought wise to establish protective regulations and to place a bounty on its chief enemy, a hawk…" It is so because it is so, however they argued "The safety-valve of all speculation is: It might be so. And as long as that might remains, a variable deeply understood, then speculation does not easily become dogma, but remains the fluid creative thing it might be."

Explorers they had been. The real pictures were in their minds "bright with sun and wet with sea water and blue or burned, and the whole crusted over with exploring thought". Despite what they say their trip was service to science, their observations, and the thousands of little animals packed in jars; but they did not think of them as "cut off from the tide pools of the gulf."

The following four images were graciously provided by the California Academy of Sciences, Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology. Each image is copyrighted material © 2012 California Academy of Sciences, reproduction is not allowed without permission from the California Academy of Sciences.Heliaster kubiniji

"…some animals began to emerge as ubiquitous. Heliaster kubiniji, the sun-star, was virtually everywhere, but we did observe that the farther up the Gulf we went, the smaller he became", Sea of Cortez, Chapter 16

.jpg)

Copyright © 2012 California Academy of Sciences, all rights reserved

.jpg)

Copyright © 2012 California Academy of Sciences, all rights reserved

Eucidaris thouarsii

"The club-spined sea-urchins [Eucidaris thouarsii] were numerous in their rock niches. They seemed to move about very little, for their niches always just fit them, and have the marks of constant occupation", Sea of Cortez, Chapter 10

.jpg)

Copyright © 2012 California Academy of Sciences, all rights reserved

Astrometis sertulifera

"In this zone verrucose anemones were growing under overhangs on the sides of rocks and in pits in the rocks. There were also a few starfish [Astrometis sertulifera]…", Sea of Cortez, Chapter 21

.jpg)

Copyright © 2012 California Academy of Sciences, all rights reserved

Suggested Reading:

Renaissance Man of Cannery Row: The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts by Edward F. Ricketts, 2002

Between Pacific Tides by Edward F. Ricketts and Jack Calvin, 1939 (the second 1948 edition has a foreword by John Steinbeck)

The Marine Decapod Crustacea of CaliforniaGoogleBook by Waldo L. Schmitt, 1921 (with Special Reference to the Decapod Crustacea Collected by the United States Bureau of Fisheries Steamer Albatros in Connection with the Biological Survey of San Francisco Bay during the Years 1912-1913)

The Pearl by John Steinbeck, 1945, first published in Woman's Home Companion in December 1945 under the title The Pearl of the World. The pearl is based on a Mexican folktale reported in Sea of Cortez. Excerpts from Sea of Cortez: "It is a proud thing to have been born in La Paz, and a cloud of delight hangs over the distant city from the time when it was the great pearl center of the world. The robe of the Spanish kings and the stoles of bishops in Rome were stiff with the pearls from La Paz"; "He went to La Paz with his pearl in his hand and his future clear into eternity in his heart".

John Alan Maxwell's painting for The Pearl of the World

Historia de la Antigua ó Baja California by Francisco Javier Clavijero, 1789, first Mexican edition 1852

"Clavigero, a Jesuit of the eighteenth century, had seen more than most and reported what he saw with more accuracy than most", Sea of Cortez, Chapter 1, and "The observations set down in his history of Baja California are surprisingly correct, and if not all true, they are at least all credible", Sea of Cortez, Chapter 8

Suggested Movie:

La Perla, 1947, directed by Emilio Fernández with actors Pedro Armendáriz (Kino) and María Elena Marqués (Juana), based on Steinbeck's novel The Pearl, released in the United States in 1948 (Steinbeck developed film project in 1944, and worked with Fernández on the film in 1945, the year he completed the draft of the novel)

Suggested Songs:

By the Beautiful Sea, performed by Billy Murray (the 'Denver Nightingale') and the Heidelberg Quintet, written by Harold R. Atteridge and Harry Carroll, 1914

Tom Joad - Words, music and performance by Woody Guthrie, 1940

Minst.org Online Library Index