Science and the Founding Fathers by I. Bernard Cohen

Author: P. Pennywagon, Ph.D.Copyright © 2012 Mednansky Institute, Inc.

The science of government it is my duty to study, more than all other sciences; the arts of legislation and administration and negotiation ought to take the place of, indeed exclude, in a manner, all other arts, from John Adams, in a letter to Abigail Adams, after May 12, 1780

The influence of science on the Founding Fathers' political thought seems almost impenetrable. By identifying scientific sources in political documents drafted by the Founding Fathers - particularly Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and James Madison - 'Historian of Science' I. Bernard CohenFootnote1 sheds some light on the subject.

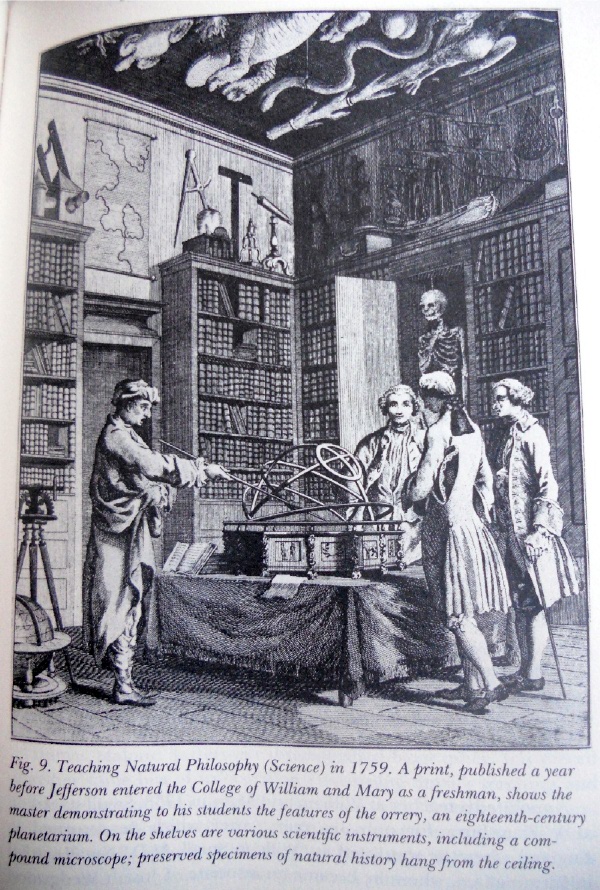

The Founding Fathers' scientific fervor is at first particularly well established by Cohen. Jefferson, Franklin, Adams and Madison were naturally immersed in science; Jefferson anticipated "the tranquil pursuits of science", his "supreme delight", Franklin was a distinguished scientist, Adams was educated in science which he regretfully deserted for political philosophy, and Madison, elected member of the American Philosophical Society, America's oldest scientific society founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin, cultivated a profound interest in the sciences.

One of the focuses of the book is the effect of science, particularly the science of Isaac Newton, on the conception of the Constitution; in brief Newton's perception of a universe governed by immutable natural forces or 'laws of motion' or 'laws of nature'. That the Constitution is a 'Newtonian' document has been the subject of much debate, and readers of Science and the Founding Fathers may form their own opinion (needless to say Cohen presents a persuasive reasoning on the question). The significance of the concept of 'natural law' or 'supreme moral law' and the appeal to the 'laws of nature' in the political philosophy of the Declaration of Independence are pondered by Cohen in Chapter 2: Science and the Political Thought of Thomas Jefferson: The Declaration of Independence. Here is his own statement: "Whatever these words may have conveyed in the sense of natural law and implied natural rights, to Jefferson and many readers of the Declaration the words 'laws of nature' would have immediately started a train of association leading to Newton's laws of motion". Thus the phrasing in the Declaration 'Laws of Nature and of Nature's God' appears to be in harmony with Newton's perception of 'natural things' in Principia, Book 3:

Blind metaphysical necessity, which is certainly the same always and every where, could produce no variety of things. All that diversity of natural things which we find suited to different times and places could arise from nothing but the idea and will of a Being necessarily existing.Benjamin Franklin - The Scientist - was creator of a new experimental science, the science of electricity, as outlined by Cohen in Chapter 3: Benjamin Franklin: A Scientist in the World of Public Affairs. "His invention of the lightning rod was of special importance because it was a dramatic demonstration of the truth of the doctrine set forth by Francis Bacon and by René Descartes, that pure or disinterested scientific research of a fundamental kind would ultimately lead to inventions of use to humankind", writes Cohen. An examination of science in the political thought of Benjamin Franklin is however impossible to achieve because, according to the experts, he never wrote extensive political statements. "He reserved his observations for those cases which science could enlighten and common sense approved. The simplicity of his style was well adapted to the clearness of his understanding. His conceptions were so bright and perfect, that he did not choose to involve them in a cloud of expressions. If he used metaphors, it was to illustrate, and not to embellish the truth" (from Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin, 1839, Volume I, Part 3). Benjamin Franklin's most cherished moral compositions have taken a place in the minds of men.

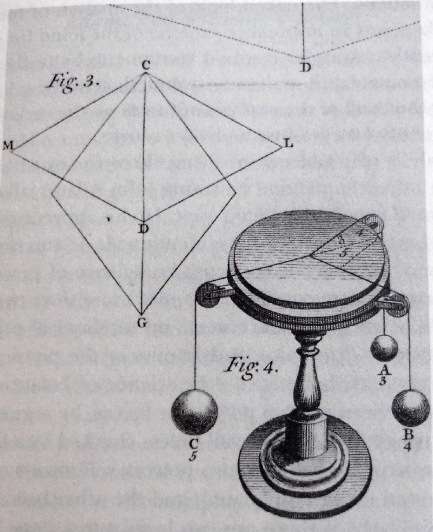

The fourth chapter, Science and Politics: Some Aspects of the Thought and Career of John Adams,brings captivating associations between John Adams' concept of a balance of power and the science of forces at rest (equilibrium) known as statics, which Adams learned at Harvard under the expert tutelage of Professor John Winthrop, a great master and famous astronomer. That an equilibrium generally requires more than two forces may have been remembered by Adams when he later wrote: "There was always a rivalry between the royal authority and that of the States, as there is now between the power of the King and that of the National Assembly, and as there ever was and will be in every legislature or sovereignty which consists of two branches only. The proper remedy then, would have been the same as it must be now, to new model the legislature, make it consist of three equiponderant, independent branches, and make the executive power one of them; in this way, and in no other, can an equilibrium be formed, the only antidote against rivalries" (emphasis added) - in John Adams' Discourses on Davila (1805).

Figure 36: Demonstration of the equilibrium of three forces

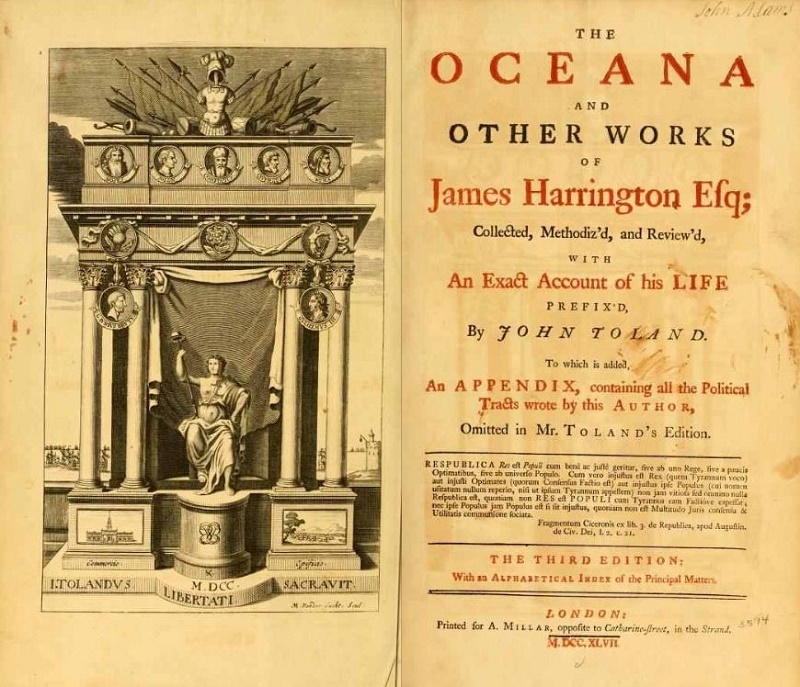

Cohen also entertains the idea that Adams' concept of balance was influenced by James Harrington's Oceana (Adams was former owner of the 1737 edition, see picture below). "There can be no doubt that Adams was aware that the concept of balance had come into current political thought in a biological … context", explains Cohen by referring to James Harrington's admiration for William Harvey, discoverer of the circulation of the blood.

Excerpt: We have wandered the earth to find out the balance of power; but to find out that of authority we must ascend, as I said, nearer heaven, or to the image of God, which is the soul of man. The soul of man … is the mistress of two potent rivals, the one reason, the other passion, that are in continual suit; and, according as she gives up her will to these or either of them, is the felicity or misery which man partakes in this mortal life.… Now government is no other than the soul of a nation or city: wherefore that which was reason in the debate of a commonwealth being brought forth by the result, must be virtue; and forasmuch as the soul of a city or nation is the sovereign power, her virtue must be law.

The final chapter, Science and the Constitution, demonstrates how science was used by the Founding Fathers as a source of metaphors and analogy. "The Founding Fathers used science as a source of metaphors because they believed science to be a supreme expression of human reason", concludes Cohen. In particular, James Madison made used of scientific metaphors in The Federalist (later The Federalist Papers), a collection of essays written in favor of the constitution. In Federalist No. 10, he wrote: "Liberty is to factionFootnote2 what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency."

Footnotes:1I. Bernard Cohen (1914-2003) was Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University, he has authored many books including The Newtonian Revolution (1980), PDF at Library of Congress (sample), and Benjamin Franklin's Science (1990)

2By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community, James Madison in Federalist No. 10

Miscellanea:

Notes on the State of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson, 1786 (private French language edition), 1787 (first public English language edition)

Discourses on Davila by John Adams, 1805. Excerpt from the preface: "The maxims inculcated in these Discourses are calculated to secure virtue, by laying a restraint upon vice; to give vigor and durability to the tree of liberty, by pruning its excrescences; and to guard it against the tempest of faction, by the protection of a firm and well-balanced government"

On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals by William Harvey (1578-1657) in The Harvard Classics, Volume 38, Part 3. Excerpt: "…it is absolutely necessary to conclude that the blood in the animal body is impelled in a circle, and is in a state of ceaseless motion; that this is the act or function which the heart performs by means of its pulse; and that it is the sole and only end of the motion and contraction of the heart"

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, 1787, eBook No 1404 at Project Gutenberg

Opticks by Isaac Newton, 1704, eBook No 33504 at Project Gutenberg (fourth edition)

Adagio for Strings by Samuel Barber, Leopold Stokowski and His Symphony Orchestra, the American Symphony Orchestra, 1968

Concord Sonata by Charles Ives, pianist John Kirkpatrick, 1945. Charles Ives dedicated his Essays before a sonata (1920) to 'those who can't stand his music' and the music to 'those who can't stand his Essays', and respectfully dedicated both to 'those who can't stand either', EBook #3673 at Project Gutenberg

Symphony No. 9 'From the New World' by Antonín Dvořák, Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Rafael Kubelík (recorded 1951)

Figure 9 from Science and the Founding Fathers by I. Bernard Cohen

Minst.org Online Library Index