'The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever' by Ignaz Semmelweis

Author: P. Pennywagon, Ph.D.Copyright © 2015 Mednansky Institute, Inc.

"Fate has chosen me as the representative of those truths that are laid down in this essay. It is my inescapable obligation to support them. I have given up the hope that the importance and the truth of the matter would make all controversy unnecessary", from the preface of The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever by Ignaz Semmelweis, dated August 30, 1860

The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever by Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) resulted from thirteen years of unfulfilled expectations by the author in bringing the truth forward, and from the thrust to advocate what were his own convictions. When, in July of 1846, Semmelweis assumed his first position as assistant at the large maternity clinic in Vienna, childbed fever, or puerperal fever, was taking many women's lives. Semmelweis rapidly recognized not only therapy was unsuccessful but also, based on some clear observations, the accepted etiology of childbed fever could not possibly be accounted for. Undoubtedly variations in mortality rates between different adjoining clinics could not be justified by undefined telluric influences or other ill-thought explanations, as clearly explained and documented in chapter 1: Autobiographical Introduction. He confidently stated "…the disease is endemic - a disease due to causes limited by the boundaries of the hospital", however his honesty prevailed as he wrote "Delivery with prolonged dilatation almost inevitably led to death. Patients who delivered prematurely or on the street almost never became ill, and this contradicted my conviction that the deaths were due to endemic cause". Then chance favored his prepared mind when a professor of forensic medicine died from a disease identical to childbed fever, after he was pricked with a knife which had been used for an autopsy. "I was compelled to ask whether cadaverous particles had been introduced into the vascular systems of those patients whom I had seen die…" In May 1847, Semmelweis introduced chlorine washings for cadaverous material-contaminated students, which resulted in a significant decrease in mortality rates. Differences in mortality rates between clinics could then be understood as students were performing autopsies in only one of the clinics. His uncompromised convictions were met with the visionary statement "…air could also carry decaying organic matter".

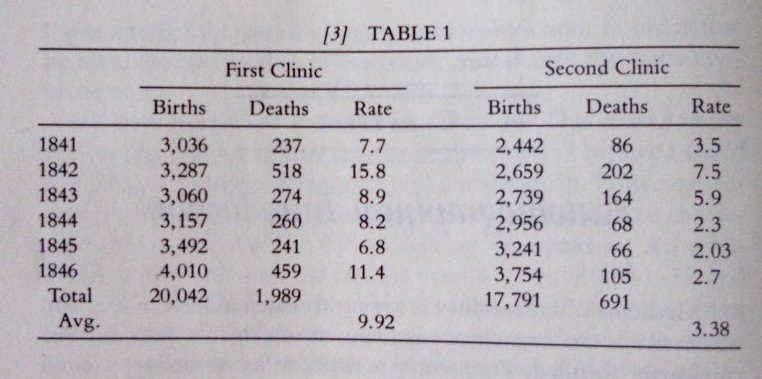

Table 1 for the 1983 edition of The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever

"From the time the first clinic began training only obstetricians until June 1847, the mortality rate in the first clinic was consistently greater than in the second clinic, where only midwives were trained", from page 64 of the 1983 edition (note the average rate at the second clinic was likely misprinted, it should be slightly higher than reported)

In chapter 2: The Concept of Childbed Fever, Semmelweis emphasized the degree of decomposition of organic matter was related to childbed fever. Sources of infection were various and generally transmitted by attendants' hands, blood-soiled linen and contaminated instruments (a footnote in chapter 2 indicates Semmelweis' critics delayed adoption of prophylactic measures by erroneously stressing corpses were the only source of infection). Semmelweis also argued childbed fever was not a contagious disease, in disagreement with others practitioners. Particularly in 1843, Oliver Wendell HolmesFootnote 1 concluded not only was the disease contagious, but also "frequently carried from patient to patient by physicians and nurses". For Semmelweis the disease could not be transmitted in the absence of 'cadaverous particles' (we now know bacteria causing childbed fever do feed on decaying matter), and death was caused by a type of pyemia (septicemia).

Chlorine hand washing in the prevention of childbed fever was desperately defended by Semmelweis in both chapter 3: Etiology and chapter 5: Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. The opponents to chlorine wash, he declared, were not likely to use chlorine conscientiously - a fact which was later on documented (see chapter 6, footnote 32). He implored "all governments to proclaim such laws [forbidding those engaged in maternity hospitals from activities likely to contaminate their hands] in order that the childbearing sex will not be further decimated, in order that life yet unborn will not be infected with seeds of death by those very persons who are called to protect life". In chapter 3, his conviction that childbed fever is not a contagious disease is further reiterated as he observed "Obstetricians carry the [decaying] matter on their hands for hours and even days without harming themselves. … If the epidermis is removed by an injury, however, the disease is generated".

Ignaz Semmelweis washing his hands in chlorinated lime water before operating (from Otto Bettmann's Archive)

In the final chapter: Reactions to My Teachings: Correspondence and Published Opinions, Semmelweis reported the praise he received, and 'conscientiously' everything said against his teachings, in order to bring physicians to the truth. He was criticized by his opponents for two specific cases he had previously mentioned. The first case, a woman with a carious knee, transmitted childbed fever without having been herself contaminated most likely because, unlike the victims who had "uteruses already lacerated", she had healthy genitals. The second case related to a woman discharging medullary carcinoma of the uterus. She also did not self-contaminate however it remained unclear if her cancerous genitals were exposed to contamination (to be prone to infection the inner surface of the uterus is, in Semmelweis' own words, "denuded of its mucous membrane and is therefore unusually resorbant"). Critics used these cases against him since they believed both woman should have infected themselvesFootnote 2. He exceedingly, and with exasperation, scrutinized his opponents' reasoning for rejecting his teachings. He ridiculed them, for example he wrote "They [his students] are more enlightened than the members of the Society of Obstetric in Berlin; they would laugh [Rudolph] Virchow to scorn if he attempted to lecture them on epidemic puerperal fever". Exasperation is tainted with sarcasm, for example as follows "I cannot deny my wonder at [Wilhelm Friedrich] Scanzoni's penetrating sagacity in dispensing with chlorine washings as an experiment". His 'agony' is felt by the reader as his doctrines which existed "to rid maternity hospitals of their horrors" were rejected. Sadly the final chapter suffers from redundancy and lacks particulars. Was the missionary of truth already "losing his grip on reality" as suggested (see footnote 81, chapter 6), or incensed because countless mothers and babies could have been saved?

Semmelweis was an innocent scientist, and a caring man. As he could not provide figures because some records were lost, he genuinely contended "I live in the city about which I speak, and this is sufficient guarantee that I speak the truth". He had faith in the honesty of his fellowmen as revealed by his final words "If I am not allowed to see this fortunate time with my own eyes, [when only cases of self-infection will occur in the maternity hospitals of the worlds] therefore, my death will nevertheless be brightened by the conviction that sooner or later this time will inevitably arrive". The observed facts cannot be changed. Lives were saved and posterity thus alleged, Semmelweis created knowledge for the benefit of humankind.

Medice, cura te ipsum

'The Physician' from The Dance of Death by Francis Douce (1757-1834). The design of The Physician for engraving on wood is attributed to painter Hans Holbein (1497-1543). The e-book is available at Project Gutenberg: The Dance of Death (E-book 38724)

Footnotes:

1Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894) was an American writer, physician, and the first president of the Boston Medical Library

2As regards footnote 20 in chapter 6, there was no reason to doubt Semmelweis was not legitimate in referring his readers to the original descriptions of the two cases under scrutiny and no reason to assert the two women should have been infected

Miscellanea:

On the Causes of the Endemic Puerperal Fever of Vienna by Charles Henry Felix Routh, in Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, 1849, 32: 27-40 (PMID: 20895917)

Mea Culpa & the Life and Work of Semmelweis by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, 1937, translated by Robert Allerton Parker (English translation first edition)

Excerpt: But they [of the Vienna Imperial Commission] were lacking in genius, and much of that was needed in order to disentangle the skeins of disease before Pasteur had arrived to lend his light to the mediocre. Besides, is not genius always needed in those crucial circumstances …

Semmelweis, a play by Norwegian author Jens Bjørneboe, published in 1968 by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, English language translation by Joe Martin, published by Sun & Moon Press, Los Angeles, in 1998

Excerpts: In Scene 18: "Chloride…The Great Chloride of Lime…Yes, I have faith in it, because it stings…it burns…it corrodes. Chloride–it bears a remarkable resemblance to something else that stings: it resembles truth. Because both truth and chloride of lime corrode…and it resembles truth because you learned it from a toilet cleaner and not a professor of medicine." In Scene 27: "If chloride is not promptly returned to the sewer workers and the sewer, where it belongs, it will be the job of the police to stop the propaganda. The book must not be read. We must not respond to these statistics. The method must not be tested!"

Men against death by Paul de Kruif, 1932

That mothers might live (1938), an Academy Award-winning 11 minute short by movie director Fred Zinnemann

The Death of Mélisande (1905) by Jean Sibelius, performed by Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen

"Exactly!… She was delivered on her death-bed; is that a little sign? – And what a child! Have you seen it? – A wee little girl a beggar would not bring into the world… A little wax figure that came much too soon;… a little wax figure that must live in lambs' wool… Yes, yes; it is not happiness that has come into the house…" From 'Pelléas and Mélisande', a play by Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949)

Songs My Mother Taught Me by Antonin Dvorak, performed by violinist Fritz Kreisler

'Gypsy Woman with a Baby' (1919) by Painter Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920)

Minst.org Online Library Index